Have you ever had a member on your team who greeted every new idea with “no”?

“We tried that before and it didn’t work.”

“No one would want that.”

“We’re overworked already, and there’s no way my team would be willing to add this to their plate.”

This is the sort of thing that can drive a nonprofit chief executive crazy. It’s impossible to get momentum going when you have to overcome multiple barriers just to get moving.

Checking your blind spots

On the other hand, it’s handy to have someone who is watching your back. Checking your blind spots.

When my wife and I travel together, she prefers I drive. We have an unspoken agreement that if she sees me about to do something really dumb, she’ll alert me.

Generally it goes like this, “HEY BONEHEAD! CHECK YOUR BLIND SPOT!”

She doesn’t simply “go along to get along.” And then let me drive off a cliff.

It isn’t just driving, either. Over 20 years of marriage, she has saved me from many bad decisions. And I’m super-grateful.

You need constructive conflict

So you need people around you who are willing to speak up and stop you from making bad decisions.

Not obstructionists, though. Those people will prevent you from testing the limits and pushing the boundaries. That’s when your organization loses its entrepreneurial edge and becomes bureaucratic.

What’s the balance?

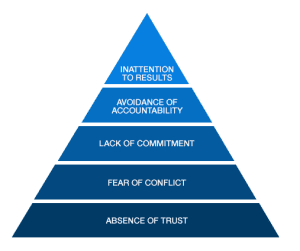

In his excellent book The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick Lencioni’s introduces the following model:

Notice the second level: CONFLICT.

Notice the second level: CONFLICT.

You need constructive conflict on your leadership team. You need people who are confident enough and feel safe enough–by establishing a foundation of TRUST–to pound the table and advocate what they believe to be true.

If you have an open marketplace of ideas, where people can speak freely without fear of recrimination, the best ideas will win.

AND, back to the graph, you will then get commitment, accountability, and attention to results.

How to know the difference between “obstruction” and “conscientious objection”

So how do you know when a member of your leadership team is objecting on conscience or simply obstructing?

First, let’s quickly review the motivation for obstructionism.

Let’s say you have a team member who has comfortably settled into a rut. He likes the current flow and is afraid a new direction will require a lot more effort. Or, she is afraid her role will shift to emphasize something she isn’t good at. Or he is afraid of looking stupid. After all, you have to be willing to do something badly as the starting point of learning to do it well.

These are all deep fears which most people have, at varying levels.

Back to the measuring stick.

Here are some signs of a conscientious objector:

- Her objections are based upon data and/or research.

- She can cite specific examples of experience she believes are applicable.

- She airs her objections within the context of the group process.

- If a decision she opposes is selected by the group fairly and openly, she will support it.

- After the meeting, she works diligently to implement the decision in support of the greater good.

Conversely, here are signs of an obstructionist:

- He relies on sweeping generalities to make his point, using words like “everyone”, “no one,” “never”, and “always.”

- He implores the team to ignore data in favor of what “feels right.”

- He refuses to support a decision arrived at fairly and openly.

- After the meeting, he spends time in coworkers’ office–with doors closed–privately lobbying his point of view and undermining the group process.

Obstructionists are a cancer on your team. You should consider getting them off your bus.

Conscientious objectors are only good for you if you listen

Sometimes I’m not a very good listener. There’s a reason my wife has to yell at me to get my attention.

One time I did drive off a cliff, figuratively speaking.

I had a senior staff member who I respected very much. Let’s call her Suzy. Suzy always maintained her professionalism, even when she was conscientiously objecting.

I had another member of the team who wasn’t pulling his weight. Let’s call him Steve.

Suzy was concerned about this on multiple levels. She wanted our organization to be outstanding in every way. She knew Steve’s underperformance was dragging us down.

She also knew that the other members of the team recognized Steve’s poor performance, and it was affecting morale.

Additionally, Suzy was loyal to me, and wanted me to be seen as a great executive director–by the team, by my board, by the community at large. She recognized that my continued allowance of Steve’s underperformance was reflecting poorly on my ability to run a great organization.

Being a consummate professional, she didn’t want to just come out and tell me that Steve sucked.

She did, however, point out on multiple occasions how Steve’s numbers were underperforming our established targets. She referenced challenges she personally encountered while working with Steve: missed meetings, missed deadlines, unrealistic requests he made of her.

Suzy gave me everything I needed to take action.

I just didn’t listen. I made excuses. I would respond, “I’m working on it.”

Truth is, I just didn’t want to deal with it. I was kicking the can down the road.

Finally, the poor performance became so obvious I was forced to make a change. I let Steve go.

And Suzy was firmly behind me. She communicated the change to her team in a way that supported me. She reassured everyone this was a positive transition. She worked extra hours during the interim until we refilled the position.

We ended up fine. But there was an undeniable loss of momentum through my inaction.

What do you think?

Do you have examples of a time when a disagreeable staff member helped you? Do you have tips for telling the difference between a conscientious objector and an obstructionist?

I’d love to hear about it! Email me or hop over to the Nonprofit Wizards Facebook page and leave a comment!

Darren Macfee is the founder of the Nonprofit Wizards. He studies the habits and practices of wizards and then shares those with the world. He also strives to be a little better every day–as a husband, as a dad, and as a business professional.